Redefining Cultural Heritage -2

When it comes to protecting heritage, it is important to understand that a heritage place has a number of values that give it a meaning, a place in society and reasons to be protected. These values vary and change. As the prominent archaeologist Dr. Gamini Wijesuriya explained in our last article (published 10 April), when planning conservation and management programmes, all these values should be taken into consideration.

“Protecting and sharing heritage requires management strategies that define and monitor property boundaries and also address the wider setting in which the property is located.”

He explained that, for World Heritage sites, boundaries should be precisely identified and regulated buffer zones, and a wider ‘area of influence’ need to be recognized for effective management.

Defining physical boundaries – the property and the setting

In general, physical boundaries are demarcated when tangible cultural heritage sites are declared as ‘National Heritage’ and in some countries, buffer zones are used. For instance, in Sri Lanka, a 400 yards distance from the boundary of a site has been identified as a buffer zone by law. “Nevertheless, these should be reconsidered when it comes to the buffer zones of World Heritage Properties as they have special requirements.”

Therefore, the values of a heritage site and specifically the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of a World Heritage site is the primary parameters for defining the three physical area(s) namely the boundary, the buffer zone, and the wider setting that management strategies need to address and for defining the varying levels of control necessary across those areas.

Distant views from the property (for example, the view of the volcano Vesuvius from Pompeii in Italy) or views of the property from certain arrival routes (for instance the Taj Mahal in India) could be important to maintaining the values of those sites.

However, other parameters will influence the definition of the physical area(s), including:

– The type of threats and their relative time frames (for instance the impact of vandalism, uncontrolled development of the built environment, climate change);

– The extent to which the management strategy involves local communities and other stakeholders (a successful participatory approach can permit reduced levels of control);

– The extent to which the management system embraces sustainable management practice.

This recognition that physical areas required are no longer where the conventionally designated site boundary falls but are in fact a series of layers undoubtedly favours protection, however, it creates new management challenges. It is also an acknowledgment that heritage places depend on their setting (and vice versa).

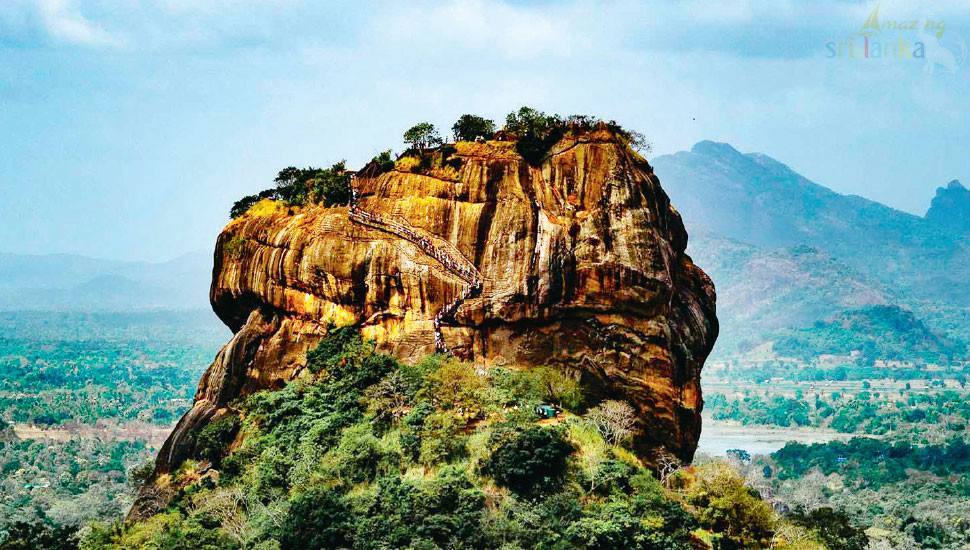

“It was in this context that the UNESCO World Heritage Committee requested an impact assessment to assess the impact of the proposed Port development in Galle at the World Heritage site of Galle Fort. Similarly, Ceylon Today carried a major article and questioned the possible impact of housing development at the Sigiriya World Heritage site on which authorities are still silent despite questions raised by UNESCO,” further explained Dr. Wijesuriya.

Ceylon Today investigated and reported this in April 2021. A high-rise apartment building was being built in the vicinity of Sigiriya in the historic landscape; which would have a great negative impact on the ancient landscape.

Placing heritage concerns in a broader framework

The expanding concept of heritage and the increased importance is given to how heritage places relate to their surroundings mark an important shift in thinking.

“Heritage places cannot be protected in isolation or as museum pieces, secluded from natural and man-made disasters or from land-use planning considerations. Nor can they be separated from development activities, isolated from social changes that are occurring, or separated from the concerns of the communities,” explains Dr. Wijesuriya.

Indeed, only fairly recently has the international community begun to appreciate the importance of conserving cultural heritage as places where social and cultural factors have been and continue to be important in shaping them, rather than as a series of monuments offering physical evidence of the past.

He also explains that, as a result, international ‘good’ practice, often led by Western management practice, has at times provided insufficient guidance and has risked eroding rather than reinforcing good traditional heritage management systems, particularly those in place for historic centres or other cultural sites which host ongoing multiple land and property uses.

The wider scope of heritage nowadays has led to many more players or stakeholders being involved in its management.

When heritage places were primarily monuments or sites under public control, the managerial authority could have a relatively free hand within the site’s boundaries. This is no longer the case. Even if a heritage place is publicly owned and managed, the site management authority will still need to work with the stakeholders and authorities involved in the area around the site. For more diffused heritage places, ownership will be much more widely spread.

In a heritage city, for example, the bulk of the historic buildings will be privately owned and many will be used for non-heritage purposes.

Areas of large rural sites will also be privately owned and may be farmed for crops or livestock. Local communities may depend for their livelihood on such beneficial uses of heritage places. Heritage practitioners will need to deal with a wide range of public authorities over issues such as spatial planning and economic development policy.

This means that heritage management authorities (practitioners) cannot act independently and without reference to other stakeholders. It is essential that the heritage bodies work with other stakeholders as far as possible to develop and implement an agreed vision and policies for managing each heritage place within its broader physical and social context. This places a high premium on collaborative working and the full and transparent involvement of stakeholders which is recommended specifically for World Heritage in its Operational Guidelines. Any management system, including the development and implementation of a management plan, needs to provide for this.

The wider obligations of heritage management

Multiple objectives now characterise the management of most heritage places. This means that a wide array of institutional and organisational frameworks (and obstacles), social outlooks, forms of knowledge, values (both for present and future generations, often conflicting), and other factors need to be evaluated. These factors often work in a complex mesh and establishing and maintaining suitable management approaches is all the more difficult. Overcoming this challenge is vital for the future of the cultural heritage places being managed.

An inclusive approach

Increased participation is necessary to address such multiple objectives: greater complexity requires advances in management practice. It should not, however, be assumed that a top-down approach is the only way to handle multiple issues. The term ‘management’ has been used in a very broad way in the heritage sector: as issues become more complex, there is a need to be more precise.

Management approaches must accommodate the shift (which has only emerged very recently in many parts of the world) to a wider, more inclusive approach to heritage management and to a greater emphasis on community engagement.

Though prepared for natural sites, the ‘new paradigm for protected areas’ developed by Adrian Phillips and re-presented in the IUCN Guidelines for Management Planning of Protected Areas in 2003 highlights very effectively the increased importance placed in recent years on a wider, more inclusive approach to heritage management and on community engagement. (In some parts of the world this was already happening.) Much of this guidance applies to cultural heritage places too.

Implications of an integrated approach to heritage management

The book explains the implications of an integrated approach to the management of natural heritage that comes from Australian research and its relevance to cultural heritage management. In their analysis, they interpret the integrated approach in three different ways: as a philosophy, as a process, and as a product that is worth studying by anyone engaged in the management of heritage. In brief, it explains: that as a philosophy: ‘an integrated approach should result in a shift of organizational cultures and participants’ attitudes towards acceptance and pursuit of cooperative approaches’; as a process, it ‘facilitates coordination between agencies, local governments, and community groups and as a product, ‘an integrated approach facilitates the development of complementary regulatory instruments.’

The research showed that changes were needed in different areas to permit an integrated approach. They grouped them into three key management areas – legislative aspects, institutional frameworks, and the deployment of resources– which are explored further in the book.

Achieving broad participation: how to make all stakeholders visible and engaged

A participatory approach to management is being promoted in various sectors but particularly in the heritage sector, given the perception of heritage as the shared assets of communities and a factor in ensuring the sustainability of those communities. The ownership of a heritage place may be widely diverse, particularly in urban areas or cultural landscapes. This is even more important for World Heritage properties where the identification of OUV implies even broader obligations and ownership, with the protection of heritage places considered as the collective responsibility of mankind as a whole, involving an international element in management.

The book refers to a series of books to help understand these newly evolved concepts. They are the World Heritage Papers No. 13, entitled ‘Linking Universal and Local Values: Managing a Sustainable Future for World Heritage’; No. 26, entitled ‘World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A Handbook for Conservation and Management; and No. 31 entitled ‘Community Development through World Heritage.’ They bring together interesting papers, a series of recommendations (some of which have influenced the management of World Heritage sites), and an overview of how much thinking has changed in recent years.

Information from the field shows that, in practice, heritage management systems are often failing to involve local counterparts. Even when community involvement does take place, the level of participation in decision-making and the capacity of local stakeholders actually to engage and make contributions are often limited.

However, there are many factors that can hinder a participatory approach and render ineffective attempts at local community involvement at heritage properties: the management system itself, a power imbalance between stakeholders, or political and socio-economic factors in the wider environment (poverty and civil unrest, or even deep-seated cultural values), are some examples.

Furthermore, a participatory approach that fails to engage all interest groups, particularly those who are often marginalised – women, youth, and indigenous peoples are common examples – can actually do more damage than good. It can lead to flawed projects because heritage specialists may have failed to be properly informed about important aspects or because of misunderstandings that then delay or block projects.

An effective participatory approach that delivers reciprocal benefits to the heritage places and to society depends on understanding:

– Who participates in decision-making, assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation processes, and how,

– Who contributes with experience, knowledge, and skills, and how,

– Who benefits economically, socio-culturally, and psychologically, and how.

Uncategorized, Ama H.Vanniarachchy, cultural heritage, Gamini Wijesuriya, Sri Lankan archaeology, SRI LANKAN HISTORY