Redefining Cultural Heritage – 3

“When we reject our origins, we become the product of whatever soil that we find ourselves planted; the colours of our leaves change as we consume borrowed nutrients with borrowed roots and, like a tree, we grow.”

—Mike Norton, Fighting For Redemption

Local communities will often depend on their heritage; whether for social identity or for their entire livelihood. But they can also deliver benefits to the heritage; it could be cultural values and/or its management. Understanding the contribution that World Heritage properties can make to society and to local and national economies is all the more urgent as greater importance is given to sustainable use and benefit-sharing for heritage.

In this light, Ceylon Today continued our conversation with prominent archaeologist Dr. Gamini Wijesuriya and in this article, the focus will be on heritage conservation and sustainable development.

“The role of cultural heritage in sustainable development can be considered the culmination of such issues [discussed in last week’s article] and is one of the most pressing concerns of heritage management in the modern world,” said Dr. Wijesuriya.

In his book, he says that, in recent years, as a result of major phenomena such as globalisation, demographic growth, and development pressure, the cultural heritage sector has started to reflect on the relationship between conservation and sustainable development. This was triggered by the realisation that, in the face of these new challenges, heritage could no longer be ‘confined to the role of passive conservation of the past’, but should instead ‘provide the tools and framework to help shape, delineate, and drive the development of tomorrow’s societies’.

Living heritage sites

It reflected, as well, a tendency to consider ‘living’ sites as part of the heritage, rather than mere monuments. These living heritage sites are considered important not only for what they tell us about the past but also as a testimony to the continuity of old traditions in present-day culture and for providing implicit evidence of their sustainability.

Heritage and sustainable development

The link between heritage and sustainable development is interpreted in different ways, depending on the specific perspectives of the various players, and a certain degree of ambiguity exists.

Should property management contribute to sustainable development or simply guarantee sustainable practices? Will heritage management systems also be evaluated in the future on the basis of how they contribute to targets such as the United Nations Millennium Development Goals? We questioned Dr. Wijesuriya.

The concept of sustainable development

As one of the most important paradigms of our time, sustainable development refers to a pattern of resource use that balances the fulfillment of basic human needs with the wise use of finite resources so that they can be passed on to future generations for their use and development.

Sustainable development is today the universally agreed and ubiquitous goal of nearly all development policies at local, national, and global levels. New approaches, stemming from recent research, are introducing innovative ways of expressing the concept of social sustainability, and terms such as ‘wellbeing’, ‘good life’, or even ‘happiness’, are finding their way into governmental policies and statistics, focusing on subjective and qualitative indicators, rather than purely quantitative ones.

“Since the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, the paradigm of sustainable development has been broadened to include three constituent but mutually supportive elements; environmental protection, economic growth, and social equity.”

The importance of an effective system of governance has also been stressed, including a participatory, multi-stakeholder approach to policy and implementation.

Relationship between cultural heritage conservation and sustainable development

In relation to cultural heritage, the issue of sustainable development can be understood in two ways:

1. As a concern for sustaining the heritage, considered as an end in itself, and part of the environmental/cultural resources that should be protected and transmitted to future generations to guarantee their development (intrinsic).

2. As the possible contribution that heritage and heritage conservation can make to the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of sustainable development (instrumental).

The first approach rests on the assumption that cultural heritage and the ability to understand the past through its material remains, as attributes of cultural diversity, play a fundamental role in fostering strong communities, supporting the physical and spiritual wellbeing of individuals, and promoting mutual understanding and peace. According to this perspective, protecting and promoting cultural heritage would be, in terms of its contribution to society, a legitimate goal per se.

The second approach stems from the realisation that the heritage sector, as an important player within the broader social arena and as an element of a larger system of mutually interdependent components, should accept its share of responsibility with respect to the global challenge of sustainability. In the current context of mounting pressure from human activities, reduced financial and environmental resources, and climate change, the contribution of heritage protection to sustainability and sustainable development could no longer be taken for granted but should be demonstrated on a case-by-case basis through each of the three pillars; the social, the economic, and the environmental dimensions

The potential of heritage to contribute to environmental protection, social capital, and economic growth is being increasingly recognised.

The artificial isolation of heritage concerns from other sectors would be simply unfeasible since external factors would ‘continue to penalise heritage practice just as isolated heritage management decision-making would penalise the relationship of heritage to its context’.

“This is evident in the factors that have affected the state of conservation of World Heritage properties over the past few years,” said Dr. Wijesuriya.

The statistics indicate that, in the great majority of cases, the problems responsible for the deterioration of these properties came from ‘beyond the confines of the site, and the manager in place, however good, (had) limited capacity for change’.

Contributing to sustainable development, within this perspective, would be not only an ethical obligation for the heritage sector but in the long term a matter of survival, especially in the present financial crisis, where public expenditure for conservation is increasingly difficult to justify.

Emphasis on the first argument (cultural heritage as a legitimate end in itself), when not corroborated by the evidence of the contribution of heritage to the other basic constituents of human wellbeing such as employment creation or other material benefits, has often placed heritage conservation in a sort of ‘special reserve’ of under-funded good intentions.

The assumption that heritage places, including of course the ‘sustainable land-use’ mentioned in the Operational Guidelines for cultural landscapes, represent models of development that are inherently sustainable remains to be demonstrated, particularly when priority is given to ‘protection’ and acceptable limits for change is not determined. This has led to a concern that, unless its contributions to the other three pillars are clearly articulated and recognised, heritage risks remain a marginal field in the wider framework of sustainable development.

Some have suggested, on the other hand, that too much attention is already being paid to socioeconomic ‘development’, and that it is crucial saving as much as possible of the heritage that has survived until now, irrespective of the immediate benefits that it may yield to local communities since this is a fundamental asset of the capital that will guarantee the development of future generations.

They advocate a strong stance in favour of conservation as a legitimate goal in itself, particularly for some outstanding places such as those included in the World Heritage List. Socioeconomic benefits deriving from heritage properties, in this perspective, would be of course desirable, but not strictly necessary to justify their conservation.

The implications of taking the second approach (in other words, heritage to contribute to the three pillars of sustainable development) are significant for the sector, involving a shift in many parts of the world in the very philosophical and ethical standpoint of conservation. There would also be important consequences for the theory and practice of the discipline.

“Heritage practitioners must understand the multiple linkages between heritage and the wider economic, social, and environmental dimensions that clarify the processes of their mutual interaction and act accordingly,” explained Dr. Wijesuriya.

They have to engage with a wide range of people with different backgrounds and expertise, and a broader group of stakeholders must be considered. Decisions about heritage conservation would no longer be left in the hands of heritage experts, but discussed among many counterparts, based on solid arguments and shared goals, to reach compromises.

According to Dr. Wijesuriya, what is probably required is a combination of the two approaches, which are not mutually exclusive; on one hand, reaffirming the cultural value of heritage by rendering more explicit its contribution to society in terms of wellbeing and happiness and on the other hand, exploring the conditions that would make heritage a powerful contributor to environmental, social and economic sustainability, with its rightful place as a priority in global and national development agendas.

Embracing initiatives that deliver mutual benefits to the property and its surroundings may not seem essential to the protection of the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), but may prove important in the long term because they tie the property into its context in a positive and enduring way, thus favouring its long-term survival. For example, the mutual benefits of promoting local skills to conserve the property, rather than training new talent from elsewhere, may only emerge in a long timeframe.

“World Heritage is a building block for peace and sustainable development. It is a source of identity and dignity for local communities, a wellspring of knowledge and strength to be shared.”

– Director-General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova – 18th General Assembly of States Parties to the World Heritage Convention

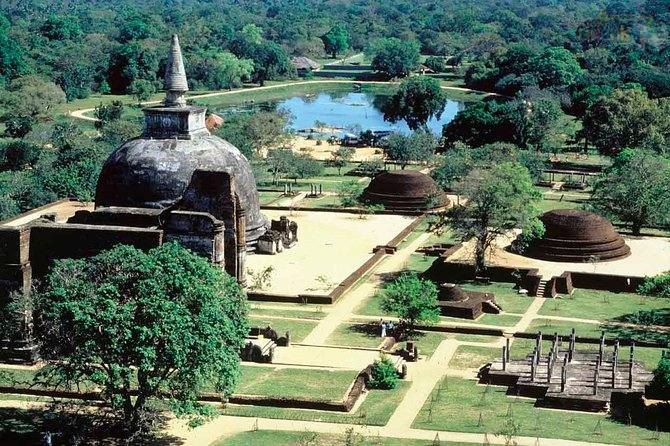

Jetavana stupa, Anuradhapura

Uncategorized, Ama H.Vanniarachchy, cultural heritage, Gamini Wijesuriya, Sri Lankan archaeology, SRI LANKAN HISTORY