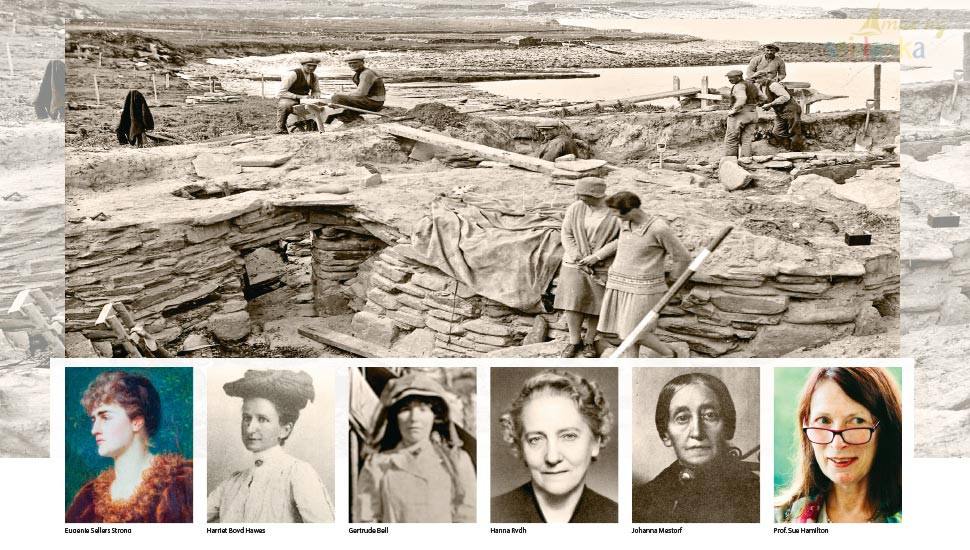

The Real Lara Crofts; Women in Archaeology

By Ama H. Vanniarachchy

“Let’s make sure women and girls can shape the policies, services and infrastructure that impact all our lives. And let’s support women and girls who are breaking down barriers to create a better world for everyone.”

—António Guterres, UN Secretary General

Archaeology was a discipline that was predominantly male-centric. At first it was ‘the rich man’s hobby’ and those who were rich enough to spare their time and money for ‘treasure hunting’ enjoyed archaeology. It was adventurous, daring and once-in-a-lifetime experience which was deemed ‘not suitable for women’. Archaeology as a discipline has its earliest origins in the 15th and 16th centuries in Europe where scholars were interested in the renaissance-period ruins of Rome and Greece. After passing few centuries as a subject of merely ‘art collecting’ and ‘treasure hunting’, the discipline of archaeology entered its phase of ‘scientific archaeology’ in the 19th century.

At early times, women were not encouraged in the field of archaeology due to the perception that women’s role was within the household being homemakers. Even after women started to work in archaeology these perceptions still existed limiting them to work in indoor spaces such as museums, laboratories and galleries, keeping them away from field work such as excavations and explorations. From 1850 onwards European universities started offering higher education courses for women, yet the social barriers did not allow them to enjoy archaeology for the fullest.

Despite all these restraints some women archaeologists were able to follow their passion in archaeology and achieve way more than their male counterparts.

Johanna Mestorf (1828-1909)

Johanna Mestorf is one of the most notable female archaeologists, known as a self-taught archaeologist. Celebrated for her exceptional skills as a scholar, the German archaeologist is credited for translating important Scandinavian archaeological work into German and in establishing the ‘three-age system’. She also wrote literature and articles and essays on ethnography and archaeology, and gave lectures on Norse mythology.

Mestorf is also known for being the first female museum director in the Kingdom of Prussia and widely believed to be the first female professor in Germany. A Street on the campus of the University of Kiel and a lecture theatre is named after her. Displayed in the Johanna Mestorf Lecture Theatre of the University of Kiel is a portrait of her. After her death, Mestorf was buried in the Mestorf family area of a cemetery in Hamburg. The Schleswig Archaeological Museum paid for the maintenance of her grave until it was cleared, and the tombstone now stands in the reading room of the museum library.

Eugenie Sellers Strong (1860 – 1943)

Eugenie Sellers Strong is the first female student to be admitted to the British school of Athens where she continued to study art history. She was an assistant director of the British School at Rome.

Madeleine Colani (1866 –1943)

Madeleine Colani was a French archaeologist born in 1866 who is well known for her archaeology research work in Vietnam and her investigations on the Plain of Jars in Laos.

Gertrude Bell (1868 –1926)

Born in 1868, Gertrude Bell was a well known British archaeologist who explored and traveled in Syria, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and Arabia. She played a major role in establishing the modern state in Iraq and she is often described as, ‘one of the few representatives of His Majesty’s Government remembered by the Arabs with anything resembling affection’.

Blanche E. Wheeler (1870 – 1936)

Born in Massachusetts, Blanche E.Wheeler is best known for her research work in Crete, and her discoveries at Gournia with Harriet Boyd Hawes. At Smith College she studied ancient art, archaeology, Greek, Latin, drawing and painting from where she graduated in 1892.

Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871 –1945)

Born in Boston, Harriet Boyd Hawes is best known as the discoverer and the first director of Gournia, one of the first archaeological excavations to uncover a Minoan settlement and palace in Crete. She is always remembered for her brave and rebellious nature and daring decisions to explore the island of Crete, just after the war when it was still unsafe.

Edith Hall (1877–1943)

Edith Hall was the first to earn a doctorate in classical archaeology from Byrn Mawr College, America. She conducted archaeology research work at Crete, and ancient Greece. Hall also researched the Etruscan culture and was in the excavation team who brought the first Mycenaean and pre-Mycenaean collection to America.

Hanna Rydh (1891 – 1964)

Hanna Rydh was born in Stockholm, Sweden and studied archaeology at the Stockholm University. After graduating in 1915, she submitted her doctoral dissertation at Uppsala University in May 1919. She was married to fellow archaeologist Bror Schnittger (1882-1924) and together they conducted archaeological excavations at Adelso and at Gastrikland. She is always remembered as an example and a role model for ‘new women’ and as a pioneer of female archaeologists.

Despite all the efforts and triumphs of these female archaeologists, the condition of the discipline has progressed, only a little. At present, a large number of female students are studying archaeology at universities but their contribution towards the discipline in a greater scope is not that satisfactory.

Especially in the Sri Lankan context, many female graduates in archaeology do not pursue a career as archaeologists due to many restraints and end up doing jobs that are unrelated to their field of study. The restraints may vary but surprisingly, most of the female graduates succeed in their postgraduate studies as well.

The social pressure as well as the sexual harassment persuades them to choose other career options, leaving behind their bread and butter. The situation is not as such only in the Sri Lankan context but true even internationally.

The director of the University College London Institute of Archaeology, Prof. Sue Hamilton, in her 2014 research paper, Under-Representation in Contemporary Archaeology states that 60 to 70 per cent of the institute’s undergraduate and postgraduate students are women, including postdoctoral researchers.

Yet, the percentage of women among permanent academic staff has never been more that 31 per cent. Her statistics further states that the percentage of women representing each academic rank at the institute is notably low with only 38 per cent of lecturers, 41 per cent of senior lecturers, 17 per cent of readers and 11 per cent of professors being female.

These low percentages of women’s contribution to the field of archaeology are a matter that should be addressed. In Sri Lanka too, women are still under-represented at the most senior levels of archaeology. Prof. Hamilton further states that, “a 2016 study found a similar pattern in Australian universities. Whilst 41 per cent per cent of academic archaeologists were women, there was an imbalance in female representation in research fellowships (67 per cent) compared to higher-ranked lecturing posts (31 per cent). This study identified a ‘two-tiered’ glass ceiling: women were less likely to obtain permanent tenure-track positions, and those that did also found it more difficult to advance to senior ranks.”

What could be the reasons for this negative status in the discipline of archaeology that occurs globally? Two major factors that can be identified are;

The social pressure / cultural perceptions Sexual harassment (verbal, emotional and physical)

Apart from regarding women as the ‘weaker sex’ and are not ‘fit enough’ to do fieldwork the society also sees women as ‘eye candy’, who are there to ‘please and serve’. In many eyes women are ‘gentle and soft’, glamorous and should be ‘looked after’, hence creating the perception of women are ‘unlikely’ to pursue a field subject such as archaeology.

The sexual harassment women have to go through in the field of archaeology is a global challenge that holds most of the female scholars from choosing field work, and limiting them to indoor work. In 2014, the Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE) surveyed nearly 700 scientists on their experiences of sexual harassment and sexual assault during fieldwork.

The survey was aimed at field researchers across a range of disciplines (anthropology, biology and so on) but archaeologists constituted the largest group of respondents. The survey confirmed that sexual harassment and assault were ‘systemic’ problems at field sites, with 64 per cent of respondents reporting that they had personally experienced harassment and 20 per cent saying that they had personally experienced sexual assault. Women, who made up the majority of the respondents (77.5 per cent), were significantly more likely to have experienced both and were also more likely to report that such experiences were occurred ‘regularly’ or ‘frequently’. The survey further stated that the targets were almost always students or early career researchers, and the perpetrators were most likely to be more senior members of the research team, although harassment and assault from peers and members of local communities were also relatively common.

Though it is not being reported much, the situation is the same or worse in Sri Lanka. Undergraduates as well as fresh graduates in the field of archaeology in Sri Lanka, face such unpleasant situations at least once in their lifetime. In almost all these cases, women do not raise their voice due to the fear of losing their degree or job. Making the situation worse, verbal sexual harassment is not considered as ‘real harassment’ by our society and such incidents are marked as ‘light’ and ‘funny’, surprisingly by the both sexes.

The 2014 SAFE survey further states that the experiences reported ranged from inadvertent alienating behaviour to unwanted sexual advances, sexual assault, and rape. Few respondents found that there were adequate codes of conduct or reporting procedures in place. The authors of the SAFE survey emphasised the significant negative impacts such experiences have on victims’ job satisfaction, performance, career progression, and physical and mental health. Therefore, it is high time to put an end to all these negativity and encourage and welcome our women to the field of archaeology by ensuring safety and security in the field.

Uncategorized